China’s Chang’e 6 spacecraft has successfully brought samples from the far side of the moon back to Earth, marking the first-ever return of materials from this scarcely seen lunar region. The historic feat signals not only China’s soaring ambitions as a rising space-exploration superpower but also the next phase of a new space race with the U.S. and its allies to establish outposts at the strategically valuable lunar south pole.

Chang’e 6’s 53-day mission

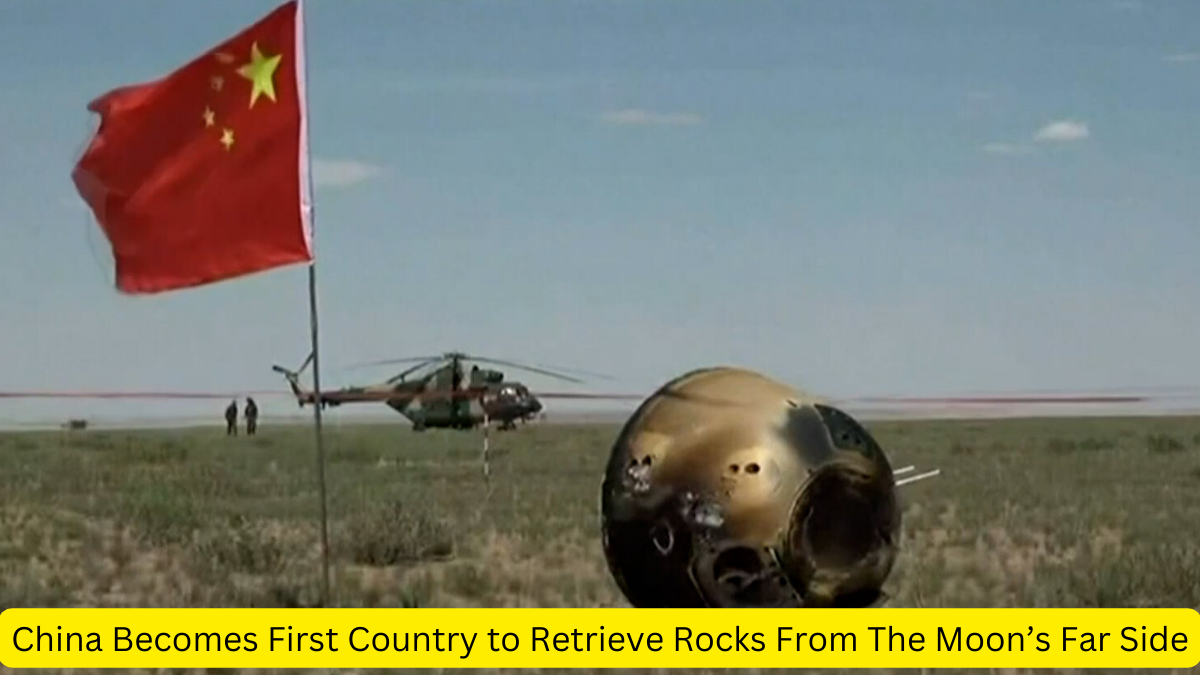

Wrapping up Chang’e 6’s 53-day mission, the spacecraft’s sample-return capsule parachuted down to a preselected site in the rolling grasslands of China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region on June 25. Packed inside the capsule are approximately two kilograms of rock and soil that were scooped or drilled from the surface and subsurface of Chang’e 6’s lunar landing site in the northeastern quadrant of the moon’s South Pole-Aitken (SPA) Basin. Thought to have been gouged from the moon’s crust and underlying mantle by a giant impact more than four billion years ago, the 2,500-kilometer-wide SPA Basin is one of the largest and oldest craters in the solar system. Samples from its depths could help solve numerous lunar mysteries-chief among them the enigma of why the moon’s far side is so relatively bereft of the craters and vast plains of frozen lava that are strewn across the Earth-facing near side.

China’s second lunar sample-return mission

Chang’e 6 was China’s second lunar sample-return mission, as well as its second landing on the far side, following the far-side touchdown of Chang’e 4 in 2019 and the retrieval of near-side samples by Chang’e 5 in 2020. No other nation has landed on the far side, let alone gathered specimens there. That makes Chang’e 6’s batch of rocks and soil a hot commodity for scientists around the globe who are vying for a chance to study them.

Opening the treasure chest

One of those eager researchers is James Head, a research professor emeritus at Brown University and an éminence grisein global planetary science. Head earned his stripes in the 1960s by scoping out near-side landing sites and training moonwalking astronauts for NASA’s Apollo program. And today he relishes his collaborations with China’s burgeoning planetary science community. The SPA Basin, Head says, is “like a treasure chest of coins from different parts of the moon, represented by individual fragments sent there by distant far-side impacts, with those fragments probably very different from one another.” And although the entire SPA Basin itself is estimated to be some 4.26 billion years old, Chang’e 6’s chosen landing spot within- at the smaller, circa 2.5-billion-year-old Apollo crater should offer an especially sweeping overview of lunar history.

Racing to the moon

China has also announced its intention to land humans on the moon by 2030, a time line rivaling that of the U.S., which plans to send astronauts to the lunar surface as early as 2026 via NASA’s much-delayed Artemis program. Both the U.S. and China are targeting the resource-rich lunar south pole for their future crewed missions, and each is presently shoring up additional support for its respective program by establishing partnerships with other nations. In collaboration with the U.S. Department of State, NASA’s Artemis Accords initiative has so far netted 43 signatory nations, each endorsing a common set of principles that are not legally binding and that the U.S. says support sustainable civil space exploration. China, together with Russia, is orchestrating an International Lunar Research Station, or ILRS, which it has declared will be “open to all interested countries and international partners.”

Sample Science diplomacy

NASA’s chief Bill Nelson has repeatedly flagged China’s flourishing lunar activities as a worrisome sign of a heated new space race akin to the frenzied competition between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union during the cold war. He did so during an April 30 House of Representatives hearing on NASA’s fiscal year budget for 2025. The south pole of the moon is important, Nelson told U.S. lawmakers, “because we think that there is water there. And if there’s water, then there’s rocket fuel—and that’s one reason we’re going to the south pole of the moon.” Because of the moon’s lower gravity-a mere one sixth of Earth’s-rocket fuel produced there can be used far more efficiently to power voyages to destinations throughout the entire solar system.

A gateway to the universe

Despite such modest diplomatic successes, however, the simmering off-world competition between the U.S. and China seems set for an eventual boiling point, with nothing less than dominion over the moon and beyond potentially in play. “Given China’s behavior on Earth, there is a good reason to worry about whether they might try to exclude others from areas where they land and establish a presence, like the polar area that has a good chance of water ice,” says Dean Cheng, a senior adviser on China for the United States Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C. Although the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, which the U.S. and China have both ratified, declares outright that no nation may claim lunar territory and that all shall have free access to all parts of the moon, the treaty also presupposes the development of lunar infrastructure and requires that “due regard” be given to the interests of others.

Made in India: Nadda Launches Indigenous...

Made in India: Nadda Launches Indigenous...

Reliance Announces ₹10 Trillion AI Inves...

Reliance Announces ₹10 Trillion AI Inves...

GalaxEye’s AI-Powered OptoSAR Satellite ...

GalaxEye’s AI-Powered OptoSAR Satellite ...