Relations between India and China have been worsening. The two world powers are facing off against each other along their disputed border in the Himalayan region. The unresolved border issue in the Himalayas has been a burden on Chinese-Indian relations for decades. In the course of their political rapprochement from the late 1980s onwards, the current Line of Actual Control (LAC) was established in 1993. However, it is not clearly defined, as there are competing territorial claims on as many as 18 places.

Buy Prime Test Series for all Banking, SSC, Insurance & other exams

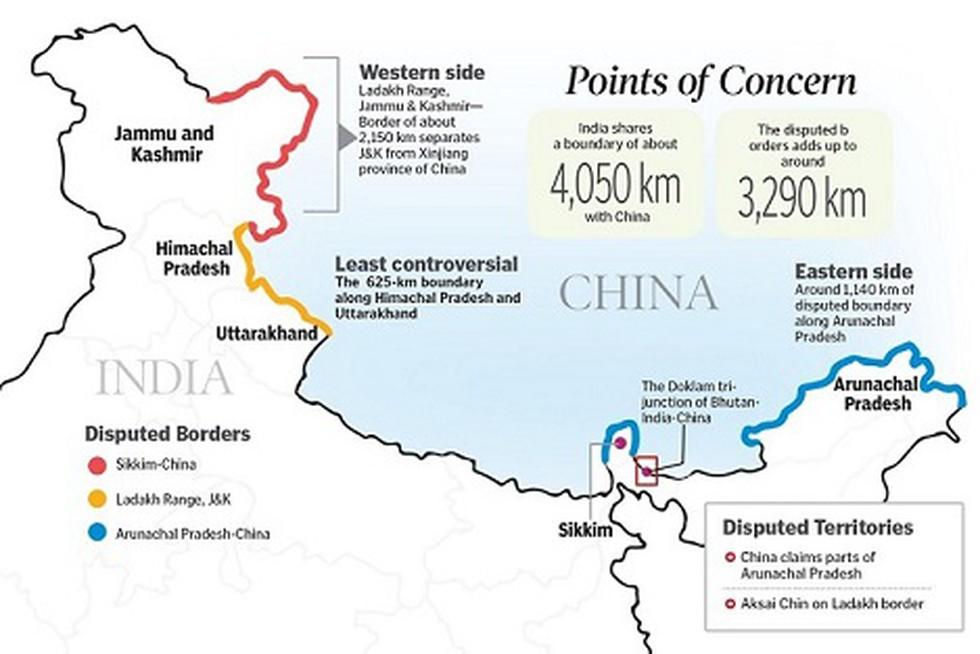

About The Border: 3-Sectors:

- The border is not fully demarcated and the LAC is neither clarified nor confirmed by the two countries.

- The LAC in the western sector falls in the union territory of Ladakh and is 1597 km long,

- The middle sector of 545 km length falls in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and

- The 1346 km long eastern sector falls in the states of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

India-China border is divided into three sectors:- - The main differences are in the Western and Eastern sectors. India sees China as occupying 38,000 sq km in Aksai Chin. In the east, China claims as much as 90,000 sq km, extending all across Arunachal Pradesh.

- The middle sector is the least disputed sector, while the western sector witnesses the highest transgressions between the two sides.

The Current Incursions: In All The 3 Sectors:

The confrontation between Indian and Chinese troops in the Himalayas, which has been ongoing since the beginning of May, has escalated into the most serious crisis in relations between the two countries in 45 years. On 15 June, for the first time since 1975, 20 Indian and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers were killed in an incident. The current crisis, unlike previous ones, has wider territorial and political dimensions. It shakes the previous border regime and strains the relationship of trust that was laboriously built up between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping. The confrontation is also a test of India’s strategic autonomy. This cornerstone of Indian foreign policy also includes the claim to an independent role in the geostrategic tensions between China and the United States in the Indo-Pacific.

What Are The Speculations Around The Current Conflict:

The current confrontation in the western sector of the Ladakh region, which belongs to Kashmir, differs in several ways from earlier ones. Firstly, this time there are territorial violations not just in one, but in five places. Secondly, it appears that far more Chinese troops are involved than in previous incidents. Thirdly, China is now claiming areas, such as the Galwan Valley, that were previously not disputed. The current confrontation seems to be due to a mixture of regional factors, such as the Kashmir conflict and growing geostrategic tensions between China, the United States, and India in the Indo-Pacific.

Kashmir and Its Consequences:

Many Indian experts see the Modi government’s decision in August 2019 to dissolve the state of Jammu and Kashmir as a trigger for the current crisis. In the course of the reorganisation of Kashmir, two new union territories were created – including Ladakh – which are administered from New Delhi. In addition to Pakistan, China had protested against this decision at the time and had pushed through an informal meeting of the United Nations Security Council on the Indian decision. China sees its interests being threatened in the Aksai Chin region, which belongs to Kashmir. The People’s Republic has occupied this region, which contains an important access road to Tibet, since the border war of 1962.

The United States & the Indo-Pacific:

The current confrontation is also related to the geopolitical rivalries in the Indo-Pacific between China on the one hand, and India and the United States on the other. India refuses to join the Chinese Silk Road Initiative, through which the government in Beijing has massively expanded its influence in India’s neighbourhood in South Asia and the Indian Ocean in recent years. This applies not only to Pakistan, which is a strategic partner of China, and to countries such as Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh, but also to the island states in the Indian Ocean.

Starting in 2017, India – together with Australia, Japan, and the United States – revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), which was created in 2007. Since then, the four states have expanded their political, economic, and military cooperation to address China’s geopolitical ambitions and its Silk Road Initiative.

Despite the rapprochement with the United States and increasing tensions with China, India continues to emphasise its strategic autonomy. This includes the claim to an independent role in the geopolitical tensions between China and the United States in the Indo-Pacific. In recent years, India and China have also repeatedly cooperated, for example in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Within the Quad, India has advocated an inclusive understanding of the Indo-Pacific, which, in contrast to the United States, has always included China.

Challenges for India’s China Policy:

Prime Minister Modi’s statement on 19 June that there had been no violation of Indian territory underlined the desire to continue with the current policy towards China, despite the gravity of the current crisis. However, India’s China policy now faces much greater challenges.

Firstly, the border regime, which was established in the 1990s, is being called into question. Following their rapprochement at the end of the 1980s, India and China signed five agreements and developed a number of confidence-building measures with regard to the LAC, such as a ban on the use of firearms in the event of incidents. Since 1989, the two states have maintained a joint working group to clarify the border’s alignment. Both sides also appointed special representatives for the border issue – by 2019 they had met 22 times in total.

Secondly, the current crisis is a setback for Prime Minister Modi as well. After the Doklam crisis of 2017, he established close personal relations with President Xi like he had with no other head of state or government. With informal summits in Wuhan in 2018 and Mahabalipuram in 2019, they sought to overcome the strategic differences between their states. Possible territorial losses would also be a stress test for Modi’s nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), since it stands for the territorial unity of the country more strongly than any other party.

Thirdly, the crisis once again shows that India has few options to put pressure on China. The People’s Republic, with which India has its largest trade deficit, has been its most important trading partner for years. In 2019 China was the third-largest market for Indian exports. Chinese technology companies have invested more heavily in Indian start-up companies in recent years. In November 2019, the Indian government withdrew at the last minute from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement, which would have increased the trade deficit with China.

Find More International News Here

Paris Olympics 2024 Medal Tally, India M...

Paris Olympics 2024 Medal Tally, India M...

Which District of Madhya Pradesh is Famo...

Which District of Madhya Pradesh is Famo...

EC Signs Electoral Cooperation Pact with...

EC Signs Electoral Cooperation Pact with...